Linbeck: Through the Decades (1998-2008)

1998-2008

Cue the new millennium. Linbeck celebrated the 2000s with countless projects and exciting ventures. Acclaimed museums, world-renowned hospitals, and once-in-a-lifetime builds fill the pages of this decade’s scrapbook. As did snowy days up north. Don your turn-of-the-century sunglasses and grab hold of your rubber bracelets. We present to you: the 2000s.

Denton A. Cooley Building – Houston, TX – 2001

If you’re a player in the Texas Medical Center, that means you’re at the center of innovation and groundbreaking research. Some of the world’s top hospital and research centers account for a mind-boggling 50 million SF of real estate in the TMC.¹ And that includes the Texas Heart Institute’s (THI) Denton A. Cooley Building.

Named for world-renowned heart surgeon Dr. Denton Cooley, the 10-story, 331,000 SF building was completed by Linbeck in 2001. This major facility would carry on the doctor’s legacy through cutting-edge research related to gene therapy, vascular cell biology, heart failure, heart transplantation, heart-assist devices, and artificial hearts.

If its medical focus wasn’t unique enough, though, its construction proved just as unique and complex.

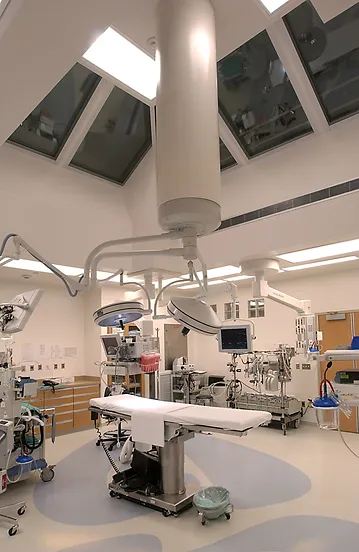

For starters, the Denton A. Cooley Building needed to satisfy the needs of two owners, the owners’ independent representatives, and two architects. Its 12 cardiovascular surgical suites were also designed with extensive input from more than 100 surgical and administrative staff members.

From the construction standpoint, the Denton A. Cooley Building was built vertically, rather than horizontally (the typical configuration). This put a unique combination of spaces on top of each other (auditorium, conference room, museum, administrative, surgical, nursing units, clean rooms, research).

To maximize floor space in the operating rooms and minimize hazards, all tubes, hoses, cords, and mechanical/electrical systems were designed to fit within the ceiling, where they could then be dropped down to each surgical table. But let’s get more specific, here… These items were added into the rooms’ perimeter crawl spaces, so they wouldn’t obstruct the glass ceiling that provided visuals to the observation deck above.

Because more than a dozen doctors and staff may be required for the hospital’s specialized surgery, the ORs also needed to be oversized and self-contained. And of course, the large medical equipment needed to fit inside this mix as well. These ORs were the first in the country—yes the country—to be designed and built specifically to accommodate automated surgical procedures and include hands-free control of OR equipment.

All of these unique construction components helped the Denton A. Cooley Building win an 2001 AON Build America Award.

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth – Fort Worth, TX – 2002

Architecture has that funny way of making something that seems so simple so significant. If you’ve ever been to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (The Modern), you can understand this feeling. If you’ve not yet been to The Modern, consider making a trip.

Designed by renowned Japanese architect Tadao Ando, The Modern is an interesting juxtaposition against Fort Worth’s art deco and classically-designed skyline. Concrete, glass, and water are all that adorn the museum—and this is what help it make a powerful statement. For as heavy as the walls look and feel, there is a sense of tranquility in the space: natural light floods the exposed galleries, while trickling water acts as the museum’s sole soundtrack.

These create the perfect backdrop for the artwork that occupy The Modern’s ever-winding, never-ending galleries.

In 2002, Linbeck completed construction of The Modern. The 153,000 SF, two-level museum was designed as a complex of five rectangular pavilions, three of which are the galleries themselves. The Modern’s predominant architectural feature is cast-in-place concrete. All of its surfaces, left as cast, are extremely smooth and extremely flat, with sharp exterior corners that do their part to highlight the structure’s precise design. The architectural concrete was cast into many challenging shapes, including flat walls with heights of 18’ and 34’, elliptical-shaped walls, elliptical roof structures, cantilevered roof slabs, and varied columns (square, round, and in the iconic “Y” shape).

In case you couldn’t tell, concrete is the trademark feature of The Modern. And it is here that the Linbeck team went above and beyond. While the team had originally planned to subcontract the architectural formwork and placement, Linbeck ended up taking direct production responsibility for this portion of work. This led our team to self-perform 37% of the project—a marker that shines a light on this team’s level of expertise. The sheer engineering behind The Modern are just as impressive and beautiful as the art within.

In 2003, the AGC of America awarded The Modern with an AON Build America Award.

MD Anderson Proton Therapy Center – Houston, TX – 2006

In Texas, we know MD Anderson Cancer Center for its groundbreaking research and cutting-edge treatments. These attributes are nothing new for the cancer treatment center—they’ve been at it since 1942.² So it is no surprise that, in 2003, they committed to bringing next-level care to their patients: proton therapy. And Linbeck was there to help.

What is proton therapy, you ask? It is an “advanced form of radiation therapy that sends a powerful beam of protons to the precise site of a tumor. Once the proton beam reaches the tumor, it conforms to its shape and depth, and only then releases its full energy. It then stops, sparing surrounding tissue.”³

The seeds for this specialized treatment were planted in the 1950s and developed over the following decades, but it was only in recent years that proton therapy became a feasible option for patients. By the time MD Anderson opened its facility in 2006, it was one of just three Proton Therapy Centers in the entire United States.

To build the 92,500 SF Proton Therapy Center—one of the most complex and complicated construction projects in the Texas Medical Center—the entire team needed to be in close collaboration at all times. Communication between Linbeck, MD Anderson, architects from Tsoi/Kobus, Hitachi, engineers, radiation oncologists and clinicians, investors, and consultants were essential to performing high-quality construction and ensuring the commissioning process would go smoothly. Especially given the facility’s highly sensitive equipment.

The Proton Therapy Center was built in two phases over the course of three years. Upon its completion, the facility was the largest of its kind using proton beam therapy. The two-story facility is essentially a concrete monolith, with as much concrete as a 20-story building. Its walls are 6’ to 8’ thick and its ceilings 8’ to 14’ thick. As an added safety precaution against radiation leakage, the majority of the building sits 42’ below ground; its height from grade is only 38′. Putting that into perspective, two-thirds of the entire building sits underground.

In addition to its research room and four treatment rooms (three with rotating gantries and one with fixed beam equipment), the Proton Therapy Center also houses control rooms for the gantries and X-ray rooms, an MRI suite, exam rooms and offices, and a conference center for 100 people.

Since completing MD Anderson’s Proton Therapy Center in 2006, Linbeck has contributed more than 10 proton therapy centers to hospitals across the country

Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart – Houston, TX – 2008

How often is it that a city debuts a new Catholic cathedral for its hometown diocese? Spoiler alert: not often. So when Linbeck was selected to construct the new Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart for the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, the weight of this project was something indescribable.

The Archdiocese envisioned a traditional European-style cathedral to replace its existing 100-year-old facility. But…minus the traditional European-style feel. While the Co-Cathedral would be shaped in a classic cruciform design, nothing else about this magnificent structure—or its construction—would be traditional.

Take, for instance, the sheer size of the cathedral. It’s not just 40,700 SF—it’s 40,700 SF of art, marble, and engineering.

Larger in volume than square footage, the interior walls of the cast-in-place concrete structure soar 83’ to 102’ in height and support an 80,000 lb copper-clad dome over the altar. There’s also a 20’x40’ stained glass “Resurrection Window,” an 8’ in diameter art glass depicting the Holy Spirit, three large rose windows, 18 sets of clerestory windows (of six windows each), and a 137’ bell tower with a custom-cast carillon of 23 bronze bells from Holland weighing a total of 30,000 lb.

But the most impactful feature upon entering the Co-Cathedral is its 20’ cross and 9’ corpus at the main altar. Suspended 35’ in the air and weighing 1,800 lb, this wooden sculpture stirred emotions among the project team during its assembly and mounting.

The intense planning effort, the integration of millions of dollars of custom artwork, the global effort to bring this masterpiece to life, the intense interest of the community and media—every element of this Co-Cathedral spotlighted the sheer gravity of what this project represented. Not just for Linbeck, but for the Archdiocese and the global community.

For its consecration ceremony, the Co-Cathedral was filled to the brim with excited and eager guests. In addition to the Archdiocese’s Daniel Cardinal DiNardo, six fellow cardinals from around the country took part in the ceremony, as well as 50 bishops, more than 500 priests and deacons, numerous local dignitaries, members of several Catholic lay organizations, and representatives from the Archdiocese’s 149 parishes.

The Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart was awarded an AON Build America Award in 2009.